This International Women's Day, STFC are looking at the women throughout history who helped make our science possible. PPD has chosen Lise Meitner, whose work transformed our understanding of the particles we study.

As I walked into St James' graveyard in Bramley, Hampshire, I stopped to tie a white ribbon on the branches of a tree, planted by the church to remember those living through conflict. It seemed a fitting pause in my search for the headstone of physicist Lise Meitner, probably best known for not winning a Nobel Prize for the discovery of nuclear fission.

The 'Tree of Hope' in the graveyard of St James' Church, Bramley, Hampshire. Photo: Emma Hattersley @STFC

Born in Vienna in 1878, Meitner's life should perhaps have led me to expect to find her resting in an unexpected place. Nothing about her could be described as predictable.

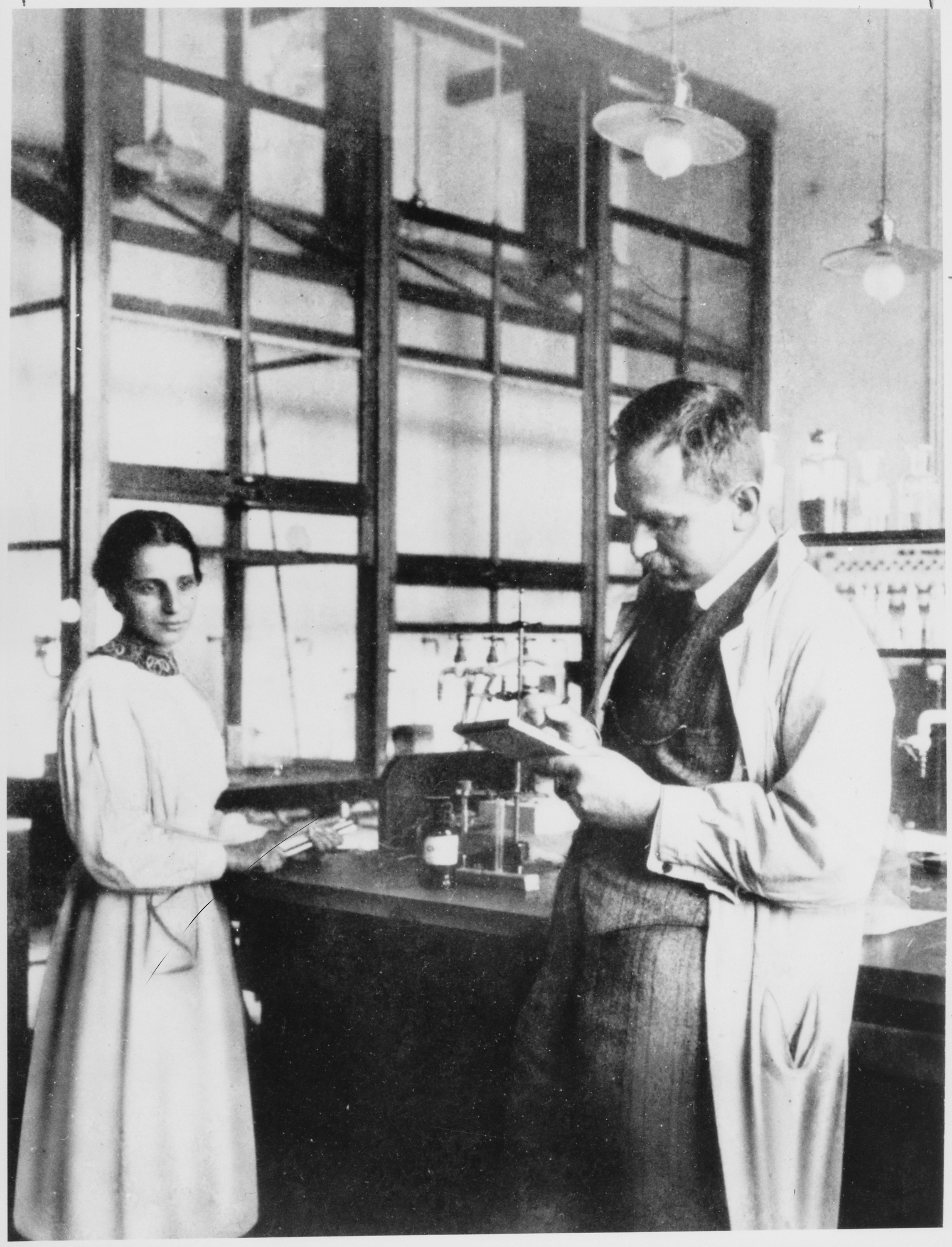

After becoming the second woman to gain a PhD in Physics from the University of Vienna, Meitner travelled to Friedrich Wilhelm University, Berlin, with no idea that women were technically excluded from attending. It was here that she first worked with Otto Hahn, her long-time collaborator and friend.

Scientifically, the pair were natural collaborators, with complimentary backgrounds and interests. Working in the basement of the Chemistry Institute, they began to research radioactive decay, where a larger nucleus emits a smaller particle, leaving behind a slightly different nucleus and some energy.

Practically, conditions were challenging. As a woman, Meitner was initially forbidden from working withHahn in his other laboratory in the main part of the Institute. This was in part due to the general legal restrictions on women attending university, as well as the reluctance of Emil Fischer, head of the Institute, to let women into laboratories. A man in Fischer's laboratory had once set fire to his own beard and left him fearful that women, if admitted, would ignite their hair. The basement was far from the reach of any Bunsen burners, but also any toilet for her to use, forcing her to use the facilities in a restaurant down the road.

Meitner worked like this for a year, when the ban on women's admittance to universities was lifted and Fischer finally allowed her to enter the Institute through the front door – and use a more convenient toilet. By the end of their first two years of collaboration, she and Hahn had discovered a new separation method for radioactive decay, and two new isotopes – atoms with the same number of protons but a different number of neutrons.

Meitner and Hahn working in their laboratory in 1913. Photo: Smithsonian Institution @Flickr

Her time at Friedrich Wilhelm proved to be only the start of a career marked by separation and division. After a pause to her research during World War 1, when she worked as an X-ray nurse-technician, Meitner returned to Berlin as the head of a new laboratory. Whilst there, she named a new element, 'protactinium', after discovering its most stable isotope with Hahn.

In 1926 she became the first woman university physics professor in Germany, but her promising career came under threat when Adolf Hitler rose to power 7 years later. Meitner, who was of Jewish descent, soon realised she needed to flee Germany. Carrying a diamond ring given to her by Hahn for emergencies, she escaped by train to the Netherlands before moving on to Stockholm, Sweden.

Safe, but separated from her colleagues, friends and possessions, Meitner found her new life as a junior researcher incredibly difficult, particularly compared to her prestigious position in Berlin. Nevertheless, she continued to collaborate by letter with Hahn, who had been studying uranium with his colleague Fritz Strassmann.

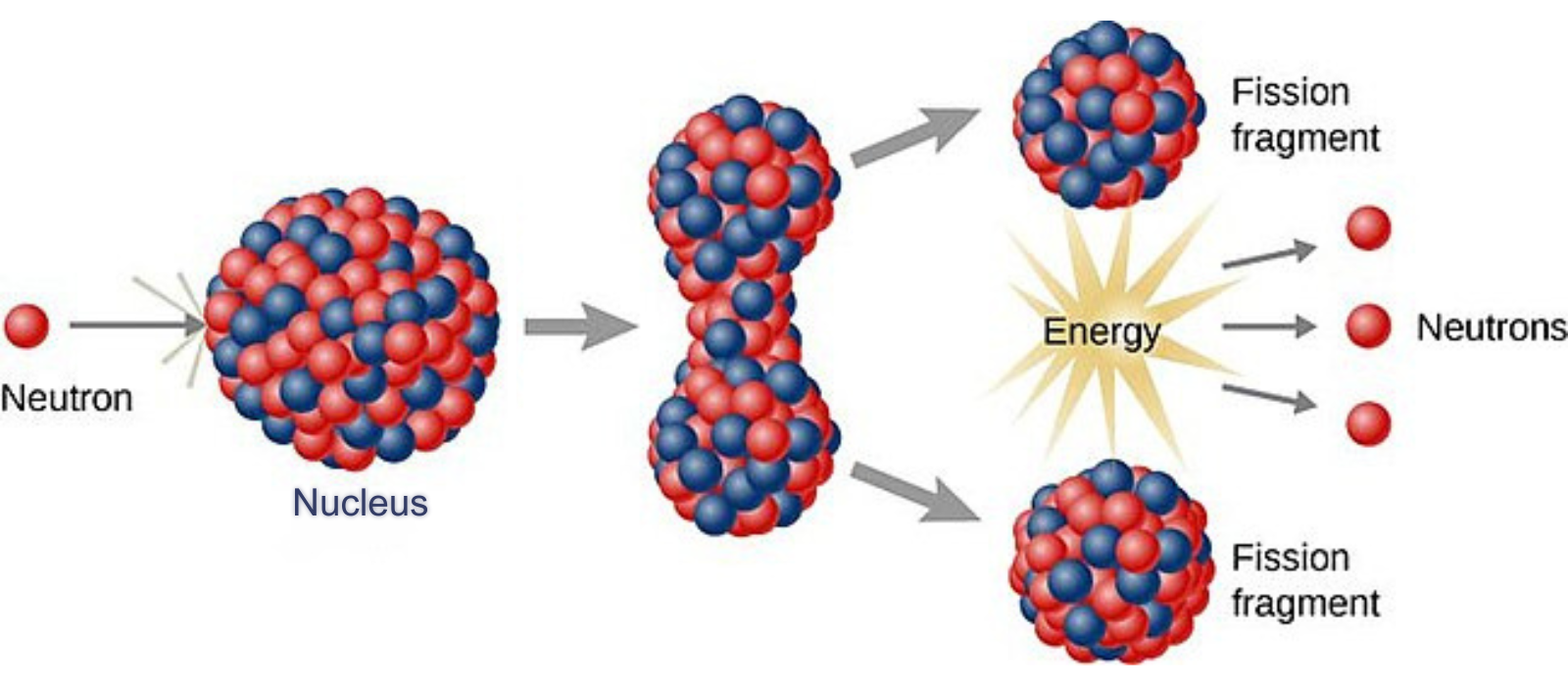

In December 1938, they found that hitting a uranium nucleus with a neutron left behind barium – a much lighter element. No known method of radioactive decay could explain how this could happen, so Hahn wrote to Meitner straight away to see if she could describe the physics. Walking through the snow over the Christmas holiday as her nephew, Otto Frisch, skied beside her, the pair realised that Hahn and Strassmann had observed the nucleus of uranium splitting roughly in half.

Meitner and Frisch went on to work out the details of nuclear fission, which describes the splitting of the nucleus of an atom into two or more smaller nuclei. This can happen spontaneously, or when the nucleus is hit by a neutron. When the nucleus splits, it releases a lot of energy, and sometimes more neutrons, which can go on to cause more nuclei to split in a 'chain reaction'. This process is what drives nuclear weapons and power stations. Nuclear reactors can also be used as a source of neutrons and neutrinos for physics experiments, even facilitating the discovery of the neutrino itself in 1956.

Diagram showing the basic process of nuclear fission. Photo: Adapted, original from University Physics, OpenStax

Although Meitner and Frisch were the first to realise what Hahn had seen, he alone won the Nobel Prize for the discovery of fission in 1944. Despite receiving 49 nominations for Physics and Chemistry - several before the discovery of fission - Meitner never won a Nobel.

Her only bitterness towards Hahn, however, was his participation in the German efforts to build a nuclear bomb. She herself had refused to visit the Manhattan project when asked, declaring “I will have nothing to do with a bomb!" Despite this, the two remained close through the rest of her lives, with Meitner regularly visiting him and his family in Germany as they grew older.

Meitner with students on the steps of the chemistry building at Bryn Mawr College in April 1959. Photo: Nuclear Regulatory Commision @Flickr

Following decades of further nuclear research in Sweden, she moved to the UK to be closer to family. In the latter part of her life, she received greater recognition for her achievements and won numerous awards, including the 1966 Enrico Fermi Award, two years before she died. She asked to be buried in Bramley so she could rest near her younger brother, Walter.

A woman shaped by her challenging life and career, it is the inscription on her headstone that provided me with the most succinct summary of her character. Written by her nephew and collaborator, Frisch, it simply reads: “A physicist who never lost her humanity."

Lise Meitner's Grave. Photo: Emma Hattersley @STFC

Lise Meitner's Grave. Photo: Emma Hattersley @STFC

International Women's Day 2024: The Women Behind the Science

Find out about more women whose research has impacted STFC:

Central Laser Facility - Donna Strickland

ISIS - Katharine Burr Blodgett

Scientific Computing Department - Eleanor Dodson

Boulby Underground Laboratory - Vera Rubin